This review critically appraises the major considerations associated with oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for men who have sex with men (MSM) within the Australian context, and suggests implications for future research. Daily oral PrEP, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)/emtricitabine (FTC) has demonstrated efficacy in preventing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission in MSM with an estimated risk reduction between 44.0 – 86.7% and even up to 99%, with consistent daily adherence. However, uptake has been slow, driven by high costs, limited availability, poor acceptance, and low concept awareness. Implementation of PrEP will rely heavily on primary care providers, who are at the forefront of health care services, in identifying high-risk patients, providing education, assessing readiness, and prescribing antiretroviral medication. Clinician scepticism and reluctance to prescribe PrEP can significantly impair access to this effective preventative strategy. Future research is essential to inform the best strategies in developing programs to support PrEP uptake, utilisation, and adherence in Australia. This will require collaboration and coordination between community health organisations, the health sector, and the general public. Open label and implementation research modelling real world effects, is urgently needed to respond to this gap in knowledge and is pivotal in driving the introduction of this effective primary prevention modality in Australia.

Background

Despite biotechnical and pharmaceutical advancements in primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) notifications have been on the rise in Australia since 1999 [1]. In Australia, 27,150 persons were living with HIV at the end of 2014 and 1,081 new cases are diagnosed annually, of which 80% are attributed to men who have sex with men (MSM) [1,2]. Furthermore, undiagnosed infections in MSM account for 31% of newly acquired HIV cases in Australia [3]. This urgently calls for original and unprecedented approaches in prevention and treatment to reduce the unrelenting high rates of infection.

A single pill taken daily has been shown to dramatically reduce HIV acquisition

A promising new strategy, combining both treatment and prevention, is pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). A single pill taken daily, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)/emtricitabine (FTC) (200 mg/300 mg) has been shown to dramatically reduce HIV acquisition in uninfected, high-risk individuals [4-8]. TDF and FTC are nucleoside and nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors and synergistically stop viral replication by interfering with viral DNA polymerase [2]. These agents have classically been used to treat HIV infection and are now recommended as pre-exposure prophylaxis. Several trials have indicated that PrEP is safe and effective in preventing HIV amongst MSM [4,5], serodiscordant couples [6], and injecting drug users [8]. This prompted the United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to recommend immediate utilisation in 2012 [9]. Although PrEP was recently approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (May 2016), this costly drug is yet to be funded through the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS).

This paper focuses on critically appraising the significant considerations associated with introducing oral PrEP in the Australian MSM population, and suggests implications for future research. This review discusses the efficacy of HIV chemoprophylaxis, evaluates current awareness, accessibility and acceptance of PrEP in Australia, and finally, examines the considerations for future drug implementation within the Australian context.

Establishing efficacy of oral HIV pre-exposure chemoprophylaxis

Clinical trials investigating PrEP efficacy and safety in MSM

Research investigating the efficacy of HIV chemoprophylaxis in MSM commenced in 2005 and evidence of success was first demonstrated in the Gates Foundation-funded Phase III multinational Preexposure Prophylaxis Initiative (iPrEx) study (Table 1) [4]. Daily oral TDF/FTC was evaluated in 2499 MSM participants from the United States, South America, Thailand, and Africa [4]. Subjects were randomised into either a placebo or a daily oral TDF/FTC cohort [4]. Follow up was conducted every 4 weeks and included provision of study medications, compliance counselling, and comprehensive prevention services. In total, adjusting for modified intention-to-treat, there was a higher seroconversion rate in the placebo arm (64/1248 subjects) compared to the TDF/FTC arm (36/1251 subjects), corresponding with an overall relative reduction in HIV risk by 44% (95% confidence interval [CI] 15-63%; p = 0.005) [4]. Adherence across participants was 50% based on pill counting and self-reported data, and estimated at 51% based on plasma detection of tenofovir [4]. Longer follow up did not reveal improvements in antiretroviral efficacy (p = 0.44). Of importance, the independent contribution of access to standard preventative services (HIV/STI testing, provision of condoms, risk reduction counselling, etc.) in the final outcome analysis is unknown. However, it is likely to have contributed positively to efficacy rates.

Table 1: Major studies on oral pre-exposure prophylaxis.

| Trial and location |

Population and number of participants |

HIV risk reduction with oral PrEP |

Estimated adherence level based on detectable plasma tenofovir levels |

| iPrEx [4]

Brazil, Ecuador Peru, South Africa, Thailand, US |

2499 HIV negative MSM |

TDF/FTC 44% |

TDF/FTC 50% |

| Partners PrEP [6]

Uganda, Kenya |

4747 HIV negative heterosexual men and women with serodiscordant partners |

TDF/FTC 75%

TDF 67% |

TDF/FTC 80.6%

TDF 83.1% |

| FEM-PrEP [10]

Kenya, South Africa, Tanzania |

202 HIV negative women |

No efficacy observed |

TDF/FTC 37% |

| TDF2 [7]

Botswana |

1219 HIV negative heterosexual men and women |

TDF/FTC 62.2% |

TDF/FTC 80% |

| VOICE [11]

South Africa, Uganda, Zimbabwe |

5029 HIV negative women |

No efficacy observed |

TDF/FTC 29%

TDF 30% |

| PROUD [5]

England |

544 HIV negative MSM |

TDF/FTC 86% |

Unreported |

The open-label trial sponsored by the UK Medical Research Council, Pre-exposure Prophylaxis to Prevent the Acquisition of HIV-1 Infection (PROUD) study, evaluated the efficacy of TDF/FTC (245 mg/ 200 mg) in 544 HIV negative MSM reporting recent high-risk sexual activity (receptive anal intercourse without a condom) [5]. Subjects recruited from 13 British sexual health clinics were randomised into two cohorts – an immediate group, which received daily oral TDF/FTC at the time of enrolment, or into a deferred group, receiving the study medication one year later [5]. High levels of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) was utilised in both the deferred (n = 85) and immediate (n = 12) groups, acting as a confounding variable, thus altering final outcomes [5]. Despite this, rates of HIV were lower in the immediate group, 3/243 person-years of follow up (1.2 cases per 100 person-years) (90% CI 0.4-2.9) compared to the deferred group, 20/222 person-years (9.0 per 100 person-years) (90% CI 6.1-12.8; p = 0.0001) producing an 86.7% (90% CI 64–96%; p = 0.0001) relative risk reduction [5]. The demonstrated efficacy of PrEP was higher in this trial, compared to the iPrEx study. PROUD participants knew they were taking PrEP whereas iPrEx subjects were blinded to their treatment groups. This open label design gave participants the knowledge that they were taking PrEP that would prevent HIV, thereby improving motivation to adhere to study medication and generating overall better efficacy rates. Further non-blinded research should be conducted within the context of a real life, implementation based framework. Non-blinded study design can improve access of non-subsidized TDF/FTC to at-risk populations and heighten participant confidence and motivation while taking study medication.

Clinical trials investigating PrEP efficacy and safety in heterosexual couples and women

Two other trials reproduced similar results in serodiscordant heterosexual couples (Table 1). The Partners PrEP study indicated a 75% (95% CI 55–87%; p < 0.001) risk reduction with daily oral TDF/FTC in Kenyan and Ugandan serodiscordant couples [6]. The TDF 2 trial investigated TDF/FTC in 1219 high-risk heterosexual men and women in Botswana and demonstrated an overall 62.2% (95% CI 21.5-83.4%; p = 0.03) reduction in HIV acquisition compared to placebo [7].

In contrast, the FEM PrEP (Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Trial for HIV Prevention among African Women) and VOICE (Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic) trials did not observe any therapeutic benefit with TDF/FTC in uninfected, high-risk women (Table 1) [10,11]. In addition to investigating oral TDF/FTC, the VOICE study also evaluated oral TDF alone and tenofovir (TFV) as an antiretroviral vaginal gel [11]. Research arms in both studies were prematurely terminated following a rise in HIV infections and due to a lack of evidence to support efficacy of oral [10,11] and vaginal preparations [11]. The vastly differing outcomes between these studies and previous studies are currently the focus of investigation.

Factors influencing PrEP efficacy

Adherence and quality of drug protection

The varying rates of PrEP efficacy across the aforementioned studies can be attributed to suboptimal medication adherence rates [4-11]. Adherence was measured by pill counting and participant self-reporting. Both methods are unreliable indicators, given the potential for misreporting and the assumption that subjects had actually taken the number of pills counted [4,6,7,10,11]. Pharmacokinetic measurements of plasma tenofovir in seronegative subjects are more reliable [12].

In the iPrEx study, overall reduction in HIV risk was 44%, with a higher rate of protection of 92% (95% CI 1.7 -99.3; p < 0.001) in those with detectable plasma tenofovir levels compared to those with undetectable plasma drug levels [4].

A quantitative study analysed the impact of varying doses against antiretroviral efficacy, based on plasma tenofovir data obtained from an iPrEx substudy and a separate trial involving monitored oral TDF dosing [12]. This study found a 99% (95% CI 96 to > 99%; p = 0.016) risk reduction when PrEP was taken 7 days a week [12]. Adherence based on detectable levels of plasma tenofovir was suggested to be a key predictor of TDF/FTC efficacy in HIV prevention [4-7,12]. However, cautious interpretation of plasma drug concentrations as a sole measure of adherence should be maintained. Factors that could alter plasma levels include individual pharmacokinetic variability, pharmacogenetic responses, dosing regimens, and co-administration of other drugs [13].

Perhaps of greater clinical importance is to appreciate the factors associated with low adherence rates. In a qualitative New York study, MSM participants rated concerns about short- and long-term side effects of chronic PrEP exposure as the greatest barrier to PrEP adherence [15]. Across clinical trials, no serious events were documented, however, long-term consequences are unknown [4,5]. Self-limiting and short-term side effects, including mild nausea and headaches, were reported [4,5] along with mild elevations in serum alanine aminotransferase [10] and serum creatinine [10,11]. Future educational programs should directly address these concerns by presenting the available evidence to suitable candidates to support their informed decision to take PrEP.

Comparatively, research participants in the VOICE trial based in South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe emphasised poor cultural and social acceptance as reasons underpinning poor adherence [14]. Specifically, these barriers were the cultural stigmata of being perceived as HIV positive, fear of scrutiny, and lack of partner support [14]. Furthermore, there was a prevailing view among research participants (70%) of being at low risk for HIV acquisition, which could have undermined the motivation to take the study’s drugs [10]. In Africa, cultural, societal, and perceptual influences appeared to be the strongest barriers to adherence, while North American attitudinal studies suggested primary concerns revolved around health consequences and medication safety. Meanwhile, future research should investigate the unique Australian factors that would predispose to poor adherence, as this information is lacking in the literature.

Access to preventative health services

Adherence alone cannot fully explain the substantial variability observed in drug efficacy rates. Experimental design in these trials included comprehensive HIV/STI prevention services [4,6,7]. The exact impact of these services in contributing to medication efficacy in the final analysis is unknown, however, prevention services alongside PrEP are likely to be important for reducing HIV infection.

Although PrEP has been demonstrated to be an effective tool in HIV prevention, use of this drug is complicated by concerns over increased risky sexual behaviour and higher rates of sexually transmitted infections [15]. There is conflicting data outside of clinical trials concerning risk compensation, emphasising a need for open label implementation research to better inform these associations in Australia. Meanwhile, applications of PrEP within the Australian context should involve a synergistic, multimodal approach, which includes expansion of prevention services providing intense and frequent HIV/STI testing, behavioural counselling, and provision of condoms [16-19].

Current status of PrEP in Australia

Outcomes from the aforementioned clinical trials will shape the future landscape of HIV prevention in Australia. These studies establish PrEP as an effective tool in preventing HIV transmission in MSM [4,5]. The current status of PrEP in Australia and the likelihood of successful implementation will be led by discussion of three key factors – awareness, accessibility, and acceptance.

Awareness

Advocacy organisations, HIV foundations, and research groups have recently made strong messages supporting PrEP utilisation in Australia. These messages seem to have garnered considerable awareness of PrEP, evidenced by a 2015 Australian study reporting 76.2% of homosexual and bisexual respondents had previously heard of PrEP [20]. Despite these efforts, few Australian MSM, 38/1251 (3.0%), have ever used PrEP, [20] with utilisation more likely to be associated with high-risk sexual practices (unprotected anal sex with casual partners rather than with regular partners) (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.36, 95% CI 1.24-4.48; p < 0.10) [21]. Public health campaigns targeted at high-risk populations at sexual health clinics, at social venues, and through gay community media should continue raising awareness with the goal of improving PrEP uptake. Despite high levels of awareness, the actual utilisation of PrEP in Australia is complicated by several factors that are subsequently discussed.

There is considerable awareness of PrEP utilisation in Australia; however, funding remains unavailable

Accessibility

Oral TDF/FTC was recently approved for the indication of pre-exposure prophylaxis in Australia. However, funding to subsidise this medication remains unavailable through the Australian PBS. TDF/FTC can be acquired through participation in clinical trials, from overseas vendors at a cost of AU$1,300/year, as a prescription costing AU$13,500/year or obtained from another person prescribed TDF/FTC for HIV infection [22]. Undoubtedly, improved uptake of PrEP will require financial subsidisation and support through the PBS. From a population viewpoint, PrEP is expensive and extending coverage to all MSM would not be cost effective in the Australian context [23]. However, one study suggested PrEP would be cost effective if one dose cost less than $15/day and had > 75% efficacy rate [24]. Conflicting research demands further investigation to ascertain the specific groups best suited for this drug, taking into consideration the individual biopsychosocial benefits and cost to society.

Acceptance and attitudes

Willingness to take PrEP among uninfected or sero-status unknown Australian MSM fell from 327/1161 (28.2%) in 2011 to 285/1223 (23.3%) in 2013 (AOR = 0.83, 95% CI 0.68-1.00, p = 0.05) [25]. Another Australian study suggested that less than half of MSM (43.2%) were willing to participate in research trials evaluating antiretroviral prophylaxis [26]. These studies demonstrate negative attitudes and lack of acceptance towards PrEP. Encouragingly, however, very high-risk MSM in serodiscordant partnerships were more interested in PrEP (AOR = 3.23, 95% CI 1.48-7.05, p = 0.003), representing a group likely to derive the greatest benefit from this drug [25]. Future Australian research should be conducted to inform of the best strategies aimed at improving understanding and developing greater acceptance of PrEP amongst other MSM groups with hesitations towards antiretroviral prevention.

Future agenda for PrEP in Australia

Clinician aspects

Primary care clinics are often the first point of health care contact for many consumers in Australia, including MSM who would be suitable candidates for PrEP. A survey of 1175 physicians in the US and Canada revealed that only 9% had ever prescribed PrEP and 26% were unsure or would not prescribe PrEP to high-risk persons [27]. Multiple studies analysing physician attitudes towards PrEP describe concerns regarding real world effectiveness, non-adherence, drug resistance, toxicity, and risk compensation as reasons against PrEP [25,28-30].

Drug resistance is rare, however, can develop when PrEP is taken in acute seronegative HIV infection [31]. Management of drug resistance is challenging given that exclusion of acute infection is practically difficult in persons engaging in frequent sexual activity and delaying treatment can increase the risk of HIV infection. Close monitoring and intensive HIV surveillance after initiation of PrEP is vital in minimising the risk of HIV drug resistance [31].

Risk compensation associated with PrEP is another concern amongst clinicians. Behavioural disinhibition and risky sexual practices can increase STI incidence [32,33]. Early detection and management of STIs through frequent and routine screening every three months can reduce transmission and reduce infection incidence [32,33]. Longitudinal and real world data analysing drug resistance and risk compensation are limited. Further inquiry is needed to inform the safest and most effective therapeutic application of PrEP within the Australian context.

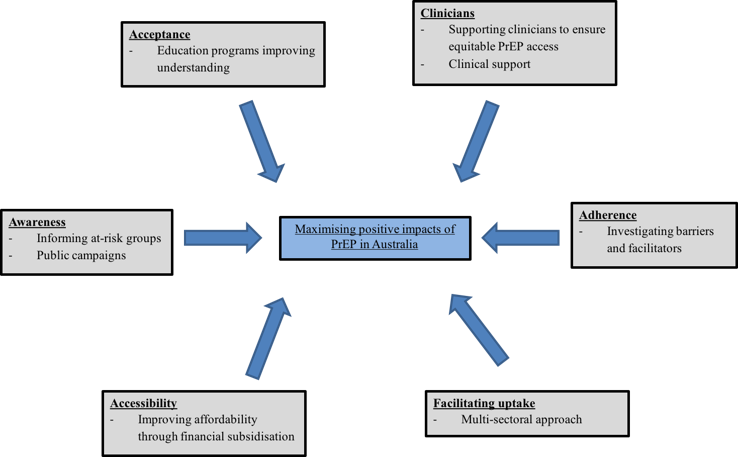

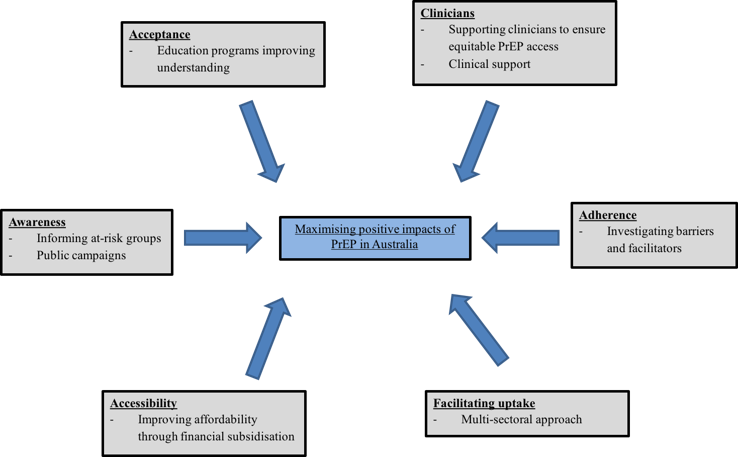

The surmounting evidence supporting PrEP in MSM is compelling and with recent approval in Australia, there has been general acceptance of this effective measure across public sexual health centres and general practice clinics. Future frameworks should embody programs supporting physician awareness of PrEP, improving comfort in discussing sexual health topics, assessing HIV risk, prescribing TDF/FTC, supporting frequent screening for STIs, managing adherence, and monitoring for resistance and toxicity (Figure 1). Primary care providers will be instrumental in improving the delivery of PrEP and monitoring for drug safety as PrEP becomes more available in Australia.

Figure 1: Factors influencing successful implementation of PrEP in Australia

Facilitating PrEP in Australia

In order to implement PrEP in Australia, facilitators for uptake and adherence will need to be considered. Respondents in US studies have named affordability of PrEP, availability of free HIV testing centres, accessibility to sexual health services, individualised counselling programs to assist with antiretroviral therapy, and a coherent understanding of what pre-exposure prophylaxis entails, as important factors facilitating uptake [15,34]. Future Australian policy development will need to account for these same issues to maximise PrEP impact.

This can only be achieved with more research to fill a major gap in the current understanding of PrEP in Australia. Future research could run as an Australian nationwide, implementation-based, open label study and assess the impact of TDF/FTC in high-risk MSM with three-monthly consultations. Outcomes would ideally inform on real world effectiveness, adherence, long-term safety considerations, risk compensation and issues surrounding utilisation. Successful PrEP rollout in Australia will require a systematic, multi-sectoral approach involving clinician training, expansion of preventative services, support from community health organisations, and increased community engagement (Figure 1). These partnerships will improve understanding, broaden acceptance, and maximise the positive impacts of PrEP in Australia.

Conclusion

This review aimed to evaluate the factors influencing PrEP implementation in Australia and to suggest an immediate research agenda. Implementation trials would bridge the gap between clinical studies and real world application through examination of PrEP within the Australian environment. Outcome variables would address adherence, awareness, accessibility, acceptance, clinician factors, cost/benefit analysis, patient motivations, and patient experiences with PrEP. Analysis of these findings will produce strategies to improve delivery of services, programs, and policies. In doing so, we optimise the successful impact of PrEP in a new primary prevention model and work towards a stronger and healthier future.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

[1] Murray JM, Prestage G, Grierson J, Middleton M, McDonald A. Increasing HIV diagnoses in Australia among men who have sex with men correlated with the growing number not taking antiretroviral therapy. Sex Health. 2011;8(3):304-10. doi: 10.1071/SH10114.

[2] Kirby Institute. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia: Annual surveillance report 2015. University of New South Wales; 2015.

[3] Wilson DP, Hoare A, Regan DG, Law MG. Importance of promoting HIV testing for preventing secondary transmissions: modelling the Australian HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men. Sex Health. 2009;6(1):19-33.

[4] Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587-99.

[5] McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, Dolling DI, Gafos M, Gilson R, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53-60.

[6] Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399-410.

[7] Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423-34.

[8] Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. 2013;381(9883):2083-90.

[9] Center for Disease Control. FDA approves first drug for reducing the risk of sexually acquired HIV infection [Internet] 2012, July [cited 2016 June 27] Available from: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm312210.htm.

[10] Van Damme, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):411-22.

[11] Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(6):509-18.

[12] Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, Buchbinder S, Lama JR, Guanira JV, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir exposure and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(151):151ra125.

[13] Anderson PL, Kiser JJ, Gardner EM, Rower JE, Meditz A, Grant RM. Pharmacological considerations for tenofovir and emtricitabine to prevent HIV infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(2):240-50.

[14] van der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, Hartmann M, Magazi B, Mathebula F, et al. Women’s experiences with oral and vaginal pre-exposure prophylaxis: the VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89118.

[15] Golub SA, Gamarel KE, Rendina HJ, Surace A, Lelutiu-Weinberger CL. From efficacy to effectiveness: facilitators and barriers to PrEP acceptability and motivations for adherence among MSM and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(4):248-54.

[16] Brookmeyer R, Boren D, Baral SD, Bekker LG, Phaswana-Mafuya N, Beyrer C, et al. Combination HIV prevention among MSM in South Africa: results from agent-based modeling. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112668.

[17] Smith DK, Herbst JH, Rose CE. Estimating HIV protective effects of method adherence with combinations of preexposure prophylaxis and condom use among African American men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42(2):88-92.

[18] Pettifor A, Nguyen NL, Celum C, Cowan FM, Go V, Hightow-Weidman L. Tailored combination prevention packages and PrEP for young key populations. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(2, S1):19434.

[19] Punyacharoensin N, Edmunds WJ, De Angelis D, Delpech V, Hart G, Elford J, et al. Effect of pre-exposure prophylaxis and combination HIV prevention for men who have sex with men in the UK: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(2):e94-e104.

[20] Lea T, Murphy D, Rosengarten M, Kippax S, de Wit J, Schmidt H, et al. Gay men’s attitudes to biomedical HIV prevention: Key findings from the PrEPARE Project 2015. Sydney: Centre for Social Research in Health, UNSW Australia; 2015.

[21] Zablotska IB, Prestage G, de Wit J, Grulich AE, Mao L, Holt M. The informal use of antiretrovirals for preexposure prophylaxis of HIV infection among gay men in Australia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(3):334-8.

[22] Australian commentary: US Public Health Service clinical practice guidelines on prescribing PrEP. Australasian Society for HIV Medicine; 2015.

[23] Schneider K, Gray RT, Wilson DP. A cost-effectiveness analysis of HIV preexposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men in Australia. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(7):1027-34.

[24] Juusola JL, Brandeau ML, Owens DK, Bendavid E. The cost-effectiveness of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in the United States in men who have sex with men. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(8):541-50.

[25] Holt M, Lea T, Murphy D, Ellard J, Rosengarten M, Kippax S, et al. Willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis has declined among Australian gay and bisexual men: results from repeated national surveys, 2011-2013. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(2):222-6.

[26] Poynten IM, Jin F, Prestage GP, Kaldor JM, Imrie J, Grulich AE. Attitudes towards new HIV biomedical prevention technologies among a cohort of HIV-negative gay men in Sydney, Australia. HIV Med. 2010;11(4):282-8.

[27] Karris MY, Beekmann SE, Mehta SR, Anderson CM, Polgreen PM. Are we prepped for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP)? Provider opinions on the real-world use of PrEP in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(5):704-12.

[28] Krakower D, Ware N, Mitty JA, Maloney K, Mayer KH. HIV providers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in care settings: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1712-21.

[29] Sharma M, Wilton J, Senn H, Fowler S, Tan DH. Preparing for PrEP: perceptions and readiness of Canadian physicians for the implementation of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105283.

[30] Puro V, Palummieri A, De Carli G, Piselli P, Ippolito G. Attitude towards antiretroviral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) prescription among HIV specialists. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:217.

[31] Lehman DA, Baeten JM, McCoy CO, Weis JF, Peterson D, Mbara G, et al. Risk of drug resistance among persons acquiring HIV within a randomized clinical trial of single- or dual-agent preexposure prophylaxis. J Infect Dis. 2015; 211(8): 1211–

[32] Baeten JM, Haberer JE, Liu AY, Sista N. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: where have we been and where are we going? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(02): S122–S129.

[33] Scott HM, Klausner JD. Sexually transmitted infections and pre-exposure prophylaxis: challenges and opportunities among men who have sex with men in the US. AIDS Res Ther. 2016;13:5.

[34] Gilmore HJ, Liu A, Koester KA, Amico KR, McMahan V, Goicochea P, et al. Participant experiences and facilitators and barriers to pill use among men who have sex with men in the iPrEx pre-exposure prophylaxis trial in San Francisco. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(10):560-6.